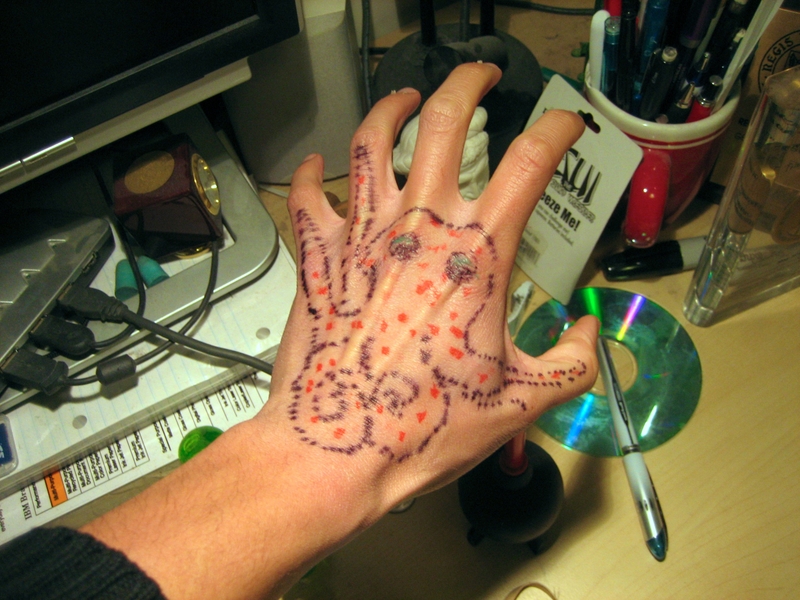

meet hubert, my octopus. he came to visit last week while i waited for some particularly long modeling jobs to execute on the darwin computing cluster (more on that later).

hubert’s timing couldn’t have been better, as his visit coincided with ned ruby‘s to mit.   here’s a picture of ned:

ned is a microbiologist from wisconsin who studies the symbiosis between the doe-eyed 3cm-long cephalopods above and a bacterium named vibrio fischeri. the talk ned gave on that symbiosis was fascinating — it was filled with precisely the kinds of wondrous stories and unbelievable facts about the natural world that convince naive students to forego the median tax bracket and become phd candidates.

he began, as microbiology talks often do, by explaining why folks shold care about microbes. in particular, he highlighted the applications of studying microbial symbioses. to paraphrase:

there are roughly 10 bacterial cells in the human body for every 1 human cell. folks estimate that each person harbors around 25,000 unique bacterial species. the human genome consists of roughly 20,000 genes; the microbial pan-genome within us consists of approximately 3,000,000.

this begs the questions: how are 3,000,000 genes simultaneously regulated in the human body? how are millions of unique metabolites and enzymes produced, transported, and employed in any coherent way?

tackling a symbiosis problem on that scale would be like trying to build a model of how individual cars affect the american nation. so, ned decided to simplify the problem. the squid he studies, euprymna scolopes (they look remarkably like ned above), enjoy the unique ability to selectively screen which bacterial species colonize certain regions of its body. specifically, the squid possesses an organ on its belly that only vibrio fischeri can live in.

and here’s where things get amazing. it turns out that the squid are nocturnal and feed near the ocean’s surface. this makes them easy prey; predators in deeper waters can easily find the squid by looking upwards and pouncing on the shadows in the moonlight. in response, the euprymna have evolved an ingenious trait known as counter-illumination. while they swim at night, the euprymna’s vibrio-filled organ glows, thereby camouflaging their shadows in the moonlight. by manipulating various muscles in the light organ that act as lenses, shutters, and filters, the squid can even control the intensity and dispersion of its anti-shadow.

how and why the vibrio bioluminesce is its own fascinating question in of itself that has already bestowed doctorates and macarthur fellowships on several researchers.

what ned talked about was studying how the euprymna and vibrio have evolved to interact with one another. now, it took him an hour to explain what he’s learned over the past decade and i haven’t got the blogging fortitude to transcribe thirty slides worth of information. besides, my memory has got the fidelity of a game of telephone. so here’s the most salient points from the presentation:

- the euprymna are actually born aseptic. within hours of being born, however, a handful of vibrio fischeri will colonize the light organ.

- over the course of the day, the vibrio make like calculators and rapidly multiply, eventually filling the light organ to capacity.

- after the evening feeding session, the euprymna contract the muscle surrounding the light organ and expel virtually all of the vibrio.

“huh?” i thought, as i heard that last bullet. why kick out beneficial bacteria?

no one’s totally certain, but a leading hypothesis is that the bacteria are actually driving the expulsion! the vibrio, perhaps not unlike pathogenic strains of e. coli, release toxins that likely degrade the membranes of the light organ, ultimately compelling the euprymna to eject the vibrio. and by getting the heave-ho, millions of vibrio are re-introduced into the water column, ready to populate new infant euprymna.

this ending to the fairy tale blew me away. on the one hand, you’ve got a bug that’s basically like cholera: it desperately wants to spread and effects that transmission by irritating mucosal membranes until the point of host expulsion. but, unlike human-affecting cholera, these vibrio are profoundly beneficial to their host in some ways, thereby providing enough incentive for the euprymna to not evolve a comprehensive mechanism for complete vibrio fischeri clearance. just a wicked cool example of how an apparently mutually beneficial symbiosis in nature can actually be a struggle between two completely opposing forces.

oh and two sidenotes:

-  ned ruby raises something like 10^5 euprymna a year in aquaria in his lab. i was dying to ask him how they tasted.

- in case you were wondering, poor hubert the hand-octopus was indeed sick with smallpox. he passed only a day after his photo was taken.